The Pacific Ocean, covering one-third of the planet’s surface, is the largest climate determinant on Earth. Oceania and Asia share a common image in the ‘River Above’ – the Pacific Ocean is the current of life and the river of Asia feeding all rivers, seasons and lives. The surface area and ocean currents absorb energy and generate thermals and other air flows, forming weather patterns and events while sustaining their movement westward.

This close relationship of water and land forms the climate as one large biome of interaction that continues to flow west, affecting the rest of the globe. This flow is life-giving and life-taking, especially as the climate is changing, biodiversity is being lost, and resources are being exhausted. The welfare of the lands and people is inextricably linked to the welfare of the seas. The traditional and Indigenous Peoples of these islands and countries are daily connected with biodiversity, are very sensitive to changes, and thus hold much of the knowledge needed for adaptation, but also call for greater climate action from the world’s large margins.

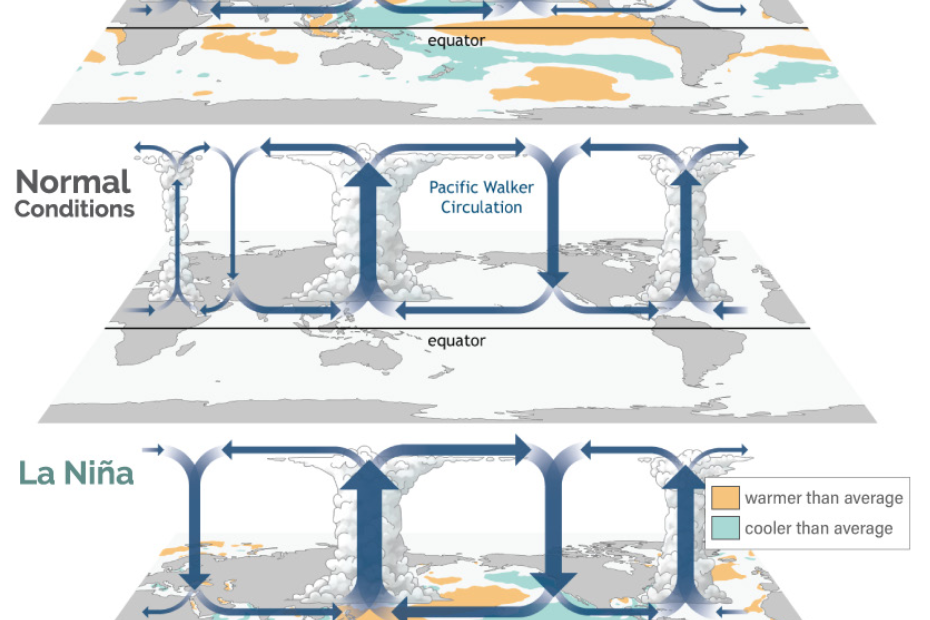

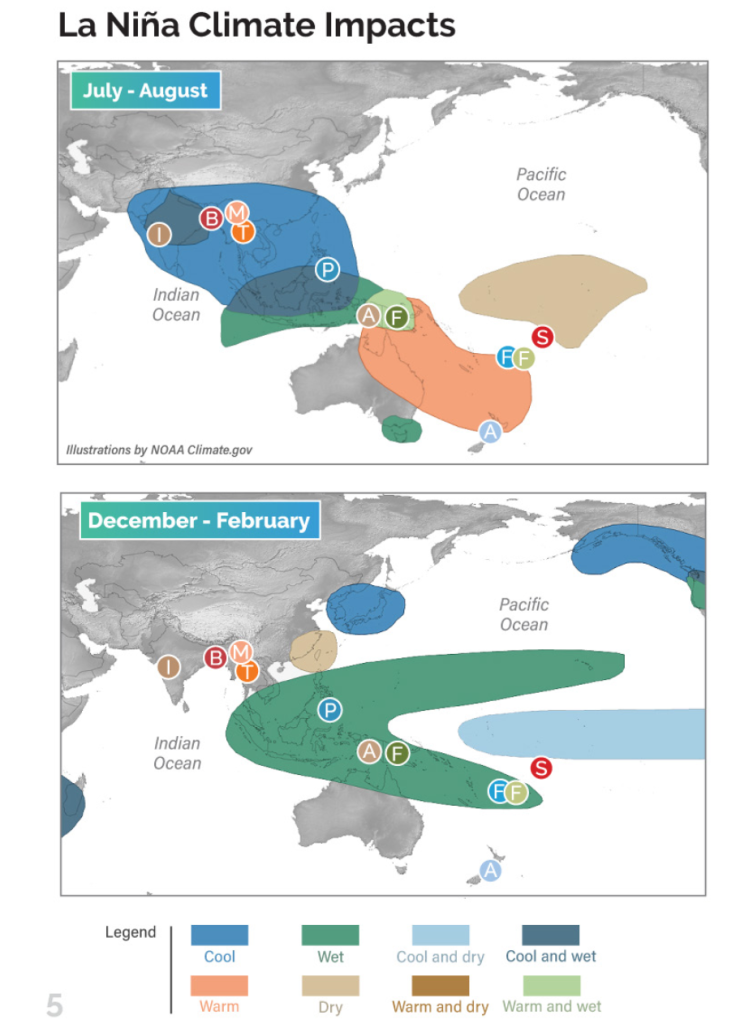

El Niño-La Niña is a natural phenomenon linked with the oscillation of the southern pole (ENSO). Climate change has made this more pronounced to the point of becoming more exaggerated and more extreme in its impact. To explain the weather patterns today and wet months becoming dry and vice versa, there is a need to understand this larger picture for the region. For the last three years, there has been an “extended” La Niña, what does this mean?

In Oceania and Asia, La Niña events lead to more widespread drought conditions. This is because the winds that normally bring moisture from the Pacific Ocean across the region are weaker during La Niña years. This has a devastating effect on agricultural communities as crops yields are reduced and water supplies dwindle. Droughts are particularly devastating in atolls that lack adequate rainwater storage capacity. La Niña can also cause problems for fishermen, as fish stocks decline in areas where the water is cooler than normal. In addition, La Niña can lead to increased flooding in other parts of the biome, and these are doubly devastating when when they happen during harvest periods.

The effects of La Niña are not always seen as negative, however. “Good weather,” meaning no rain, may be appreciated for tourism in some places, and if people have air-conditioning. It does not affect urban office work conditions. However, when drought conditions accelerate, the long-term possibilities are overwhelmingly negative, particularly in the lowlands.

Some areas and communities may benefit from improved water supply as glaciers recede or rainfall increases, but this is all in the short term. On the other hand, a greater amount of rainfall may cause more runoff, at least in the upper reaches of some river basins. In terms of more frequent and damaging floods and mudflows as well as increased water pollution, such vulnerabilities in terms of seasonality demand much greater adaptation and mitigation than in the past.

For more information and illustrations of this relationship of La Niña and climate change in Oceania and Asia, see the latest RAOEN brochure.